When conventional publishing houses and bookstores close, today as in the past, unsold stock sometimes ends up in an obscene pile. It’s one thing to know that roughly one-third of the books published in Europe before 1700 survive in only one copy; it’s quite another to be confronted with waterlogged books lying on the sidewalk.

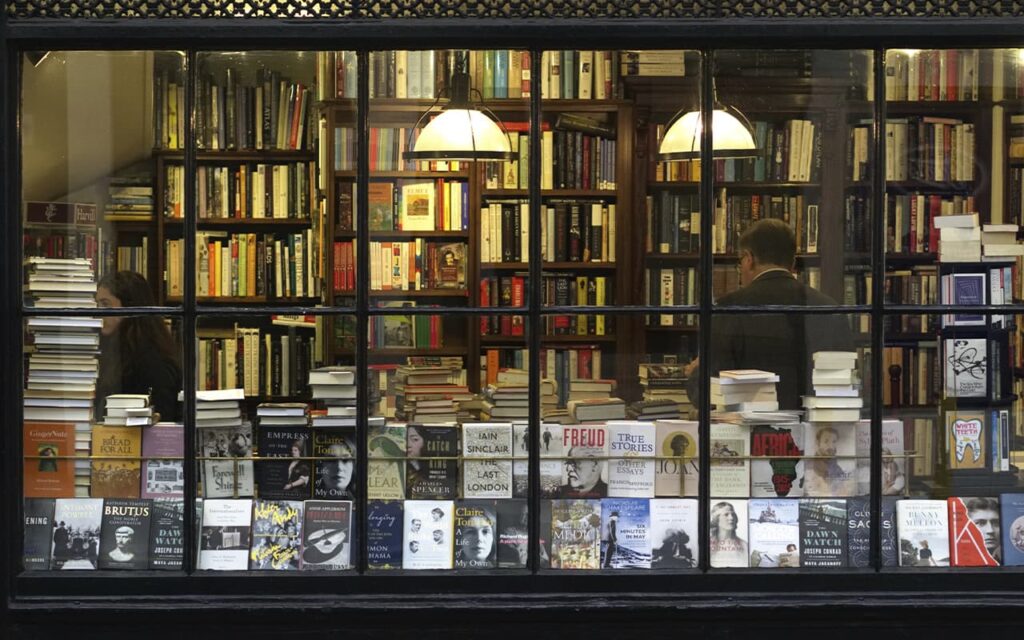

Especially for antiquarians and other independent booksellers, there is a tension between sharing knowledge and doing business. Of course, bookstores sell books and book-related products. But they can also serve as editorial offices, publishing houses, classrooms, and lecture halls, not to mention cafes, playgrounds, and reading rooms. Places of collaboration and exchange, bookstores, like libraries, can help bring a community together.

Several recent works warn against reducing bookstores to the financial bottom line. Cauter Adimi’s novel Our Wealth, translated from the French in 2020 by Chris Andrews, reconstructs the history of the bookstore that French-Algerian intellectual Edmond Charlo founded in Algiers in 1935. “In Bookstores: A Reader’s History, translated from the Spanish by Peter Bush in 2017, Barcelona-based critic Jorge Carrion weaves notes from his bookstore pilgrimages around the world with anecdotes drawn from books about books and reading. And D.W. Young’s The Booksellers, a serious 2019 documentary about the antiquarian book trade, follows a collection of collectors, archivists, librarians, and booksellers who are trying to redefine and diversify their craft by selling a seemingly minuscule number of books. There is no wide-eyed optimism in these three pieces. Their gentle depictions of bookstores and booksellers instead ask us to consider what we might be losing.

Can the lessons of the past help independent booksellers and their patrons navigate the ever-changing book world? The histories of the early modern book market, when both books and the global economy were new, do not provide a clear blueprint for how to cope with changing book technology or the implications of online book sales. They do, however, reveal a flexible sense of what books were originally like. Literary scholars José María Pérez Fernández and Edward Wilson-Lee’s The New World of Hernando Colón’s Books: Toward a Cartography of Knowledge and historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Veduven’s The Bookshop of the World: The Making and Trading of Books in the Dutch Golden Age show that books, and the book world, have never been in flux.

This knowledge may provide some reassurance to 21st century bibliophiles who worry about the future of reading. It turns out that book buyers have always sought to temper desire with caution, while booksellers have sought to balance avarice with intellectual generosity. For more than five centuries, the balance remained elusive for both sides.

The early modern book market evolves

Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Veen’s wide-ranging co-authored work, The Bookstore of the World, demonstrates that the economics of the book are best understood by looking at print culture as broadly as possible. Building on Pettegree’s previous studies of early Renaissance books and the “invention of news,” this new book looks at seventeenth-century Dutch publishing dynasties such as the Elzeviers in Leiden and the Blau and Janssonius families in Amsterdam. These family-run firms produced expensive and impressive books. Joan Blau’s large atlas, a richly illustrated collection of maps, and the Elsevier editions of Galileo and Descartes. Dutch merchants also bought books in bulk from publishers in other European countries, often paying in cash, and then reselling them at a premium at home and abroad. Skillful entrepreneurs who take into account the changing tastes of readers in both Protestant and Catholic regions, they suggested.

Meanwhile, both large and small firms competed for the predictable income and low risk associated with smaller print volumes. The highly literate and politically engaged Dutch were avid readers: newspapers, advertisements, funeral orations, dissertations, political and wedding pamphlets, postal announcements, and so on – one might say, obresillas and papers. Drawing on publishing and notary archives, Pettegree and Der Weduwen chart this iceberg of lost printed materials.

Successful Dutch publishers have also changed the book market outside the Netherlands. In Copenhagen, they pushed out local competitors. They dictated preferential terms at the critical Frankfurt Book Fair. They were decisive players in the production and trade of English bibles. And their success in Paris provoked a protectionist reaction. Amsterdam became the metaphorical bookstore of the world, but at a cost.